In defence of alternative explanations for excess deaths other than a novel deadly virus spreading from Wuhan

There are many varied possible factors contributing to excess deaths

by Dr Jonathan Engler, Professor Martin Neil, Queen Mary University of London, Professor Norman Fenton, Queen Mary University of London, Nick Hudson

On 17 Feb 2023, The Daily Sceptic published an article by Will Jones entitled, "Covid-19 and Excess Deaths: A Defence of the Virus theory."

The central thesis advanced in the article is that "the main thing driving excess deaths over the last three years... is the new SARS-like virus....".

(We are hereinafter referring to this as “the default hypothesis” because it has somehow become widely accepted, though we would argue that this owes more to promulgation of state-sponsored propaganda than to rational analysis.)

This article was aimed directly at those skeptics who have cast doubt on the default hypothesis. We believe that an alternative hypothesis—that excess deaths were primarily driven by changes to healthcare and other policies—cannot and should not be dismissed.

Overall, the central criticism of our alternative hypothesis appears to be founded in the following reformulation of the core message of the article: “we all know that it’s the spreading virus which has driven excess deaths and it might be reputationally harmful to the skeptical movement to challenge it”.

Forgive us if we ignore such an exhortation. It is somewhat ironic that the statement “we all know that” expounds the overconfidence that has got the world into the mess it is now in. Likewise, the explicit call for consensus is paying an excessive heed to the risk of reputational harm to the ‘movement’, when skeptics should be speaking out against unwarranted assumptions and claims, whatever the sources. After all, we seek the same thing: truth.

The article suggests that it is a given that excess deaths are caused by the novel virus, and that this must be the default assumption. Furthermore, the article implies that for any alternative hypothesis to displace this default explanation it must be unassailable in all its aspects, and that even a single apparent inconsistency demolishes it. This is rhetorical favoritism and assumes falsification is a one-way street.

Notwithstanding that this is not actually how scientific enquiry ought to be conducted, it belies the substantial holes in the hypothesis he advocates. Some of these holes in the ‘covid is novel and deadly’ hypothesis are helpfully revisited by Jones in an article published a few days later, which can be summarized thus: “Look, I know there are all those anomalies in the default hypothesis which cannot be explained, but these do not have to be explained because this is what we all know actually happened.”

We and a growing number of others are perplexed at the official, default narrative (in relation to the main cause of deaths). We believe that the many and varied possible factors contributing to excess deaths, from 2020 onwards, should be subject to continued forensic examination. This viewpoint has emerged as a consequence of the fact that we regard Jones’ default hypothesis of events as implausible.

To summarize, the default hypothesis (and to be fair it does not belong to Jones given that it is shared by many “thought leaders” on both sides of the covid debate), is that a deadly and novel virus spread from Wuhan for a few months before the start of 2020, and then spread throughout the globe. It then transformed itself in different places, sometimes continents or countries apart, and each outbreak occurred, with synchronicity, in early spring 2020. In all of these geographically separate locations plague-like vertiginous spikes in death rates manifested, with an intensity and duration that had never before seen before with any respiratory virus. Additionally, this only happened in particular locations in Spring 2020, the most important in relation to the global propagation of the “pandemic narrative” outside of China being Lombardy, Italy, and New York. It only lasted a few weeks, leaving neighboring locations almost completely untouched. After this novel outbreak pattern, the virus returned in late 2020 and beyond, taking forms inconsistent with this initial outbreak.

What happened in Bergamo, other parts of Lombardy and parts of New York City in March and April 2020 was quite extraordinary and, critically, played a crucial role in moulding the pandemic response in the highly influential United Kingdom, and then globally. As described here, in Bergamo deaths increased 8-10 fold in some areas. Similar carnage was seen in New York. Sudden sharp spikes in deaths, which also happened to coincide with the institution of special measures, and the fomenting of panic and fear, were observed. It is impossible to overstate the unusual nature of these peaks. Excess deaths of 800 to 1000% have never been seen before with a respiratory virus, and are totally incompatible with the qualities of a “novel” coronavirus which is supposed to have been quietly spreading for many months beforehand.

This graph of all deaths in Bergamo since 2014 reveals the extraordinary nature of what happened:

In the French heatwave of 2003 a mere 80% increase in deaths for a short period was regarded as a national scandal, having been shown to be caused largely by neglect of the elderly and a lack of basic care. This illustrates (1) how completely off-the-scale an 800-1000% increase is and (2) that short-term changes in basic care provision have the potential to cause dramatic spikes in deaths.

As can be seen from the graph below, the worst winter flu seasons saw excess death rates spike at only around 20% in France, making the 80% spike from the August 2003 heatwave stand out starkly.

Yet in percentage terms, the excess death spikes in Lombardy in March 2020 reached levels 10 times those seen in this heatwave, and 50 times those generally seen in the French winter flu season.

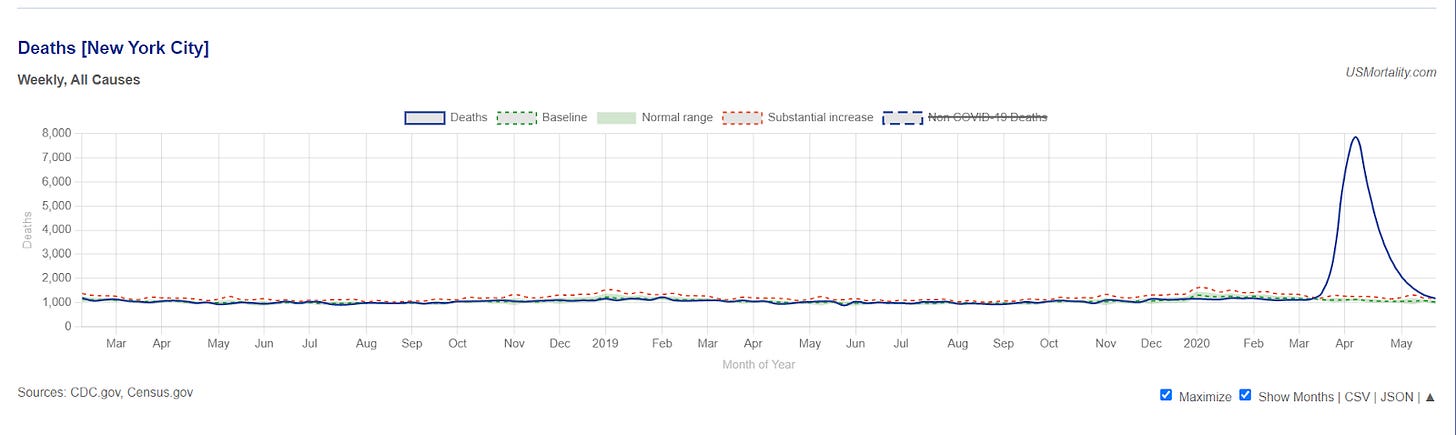

Likewise, events in New York City in Spring 2020 also look extraordinary:

Raw weekly death counts in NYC are generally around 1000-1100 and show remarkable stability. In week 15 of 2020, 7,862 people died—an increase in excess of 700% over an average week, not dissimilar to that seen in Bergamo. Put differently, week 15 in April 2020 saw the equivalent of around 7 weeks of average mortality.

It is now generally accepted that whatever “the virus” is, it had an infection fatality rate (IFR) in the same ballpark as a bad flu season. Even this is likely overstated as (1) the denominator underestimates community spread (2) the numerator will include many inappropriately treated people, as well as deaths misattributed to covid.

So in terms of pathogenicity, it wasn’t particularly distinctive compared to other respiratory viruses we regularly see, and indeed, as Jones admits, the evidence for global prior spread months before the emergency is difficult to counter. Yet, consistent with such a low IFR, this prior spread saw zero noticeable excess deaths, although clearly some over-attribution commenced a few weeks before the emergency, as several places were recording covid-related cases, at low levels, without noticeable excess deaths. Jones seems to think that the finding of any excess death prior to lockdown is a “gotcha”, falsifying the alternative hypothesis. However, this logic assumes that none of the fear and panic building in society and reported by the media is capable of inducing dysfunction in health or social care provision. We say that this dysfunction is a plausible explanation for at least some additional mortality before the governments formalized their response into legal restrictions or official policy.

One of the central planks of the default hypothesis is that there is no relationship between policy interventions and mortality. However, this shows a misunderstanding of the alternative hypothesis. Under the alternative hypothesis it is necessary to examine policy and care within the at-risk demographic within which the vast majority of deaths occurred—the elderly and otherwise frail. And when looking at explanations for mortality within this population, it is far more important to look at how they were treated compared to the wider population. Lockdown measures such as closing schools, parks, gyms, preventing indoor dining and so on may have correlated with the degree of mistreatment of the elderly, but not necessarily so, and those measures in and of themselves would not have been sufficient to contribute to the magnitude and pattern of mortality in Spring 2020.

Jones attaches some importance to the furin cleavage site (FCS) in support of the unusual nature of the virus, stating that “this essentially makes it like SARS-1 but with aerosol transmission, and so far more transmissible”. We are not actually aware of any evidence that it is the FCS itself which makes the virus aerosolized (and were in any case under the impression that SARS-1 was generally assumed to be aerosolized). Aerosolized transmission actually appears to be a property shared by mucosal respiratory viruses in general, which includes SARS-1 and other coronaviruses and influenza. Droplet and fomite transmission was always an outlier hypothesis. Moreover, to explain the extent of the mortality spikes observed, the default hypothesis requires that the virus is able to spread between people at rates that have never been seen before, that it acquires this remarkable ability suddenly when it didn’t have it before, then loses it again within a few weeks, and finally, it does so independently and near-synchronously at locations thousands of miles apart. However, if Jones is claiming (as he seems to be) that this property is a result of the FCS, nobody has argued that the FCS is something which came and went in this fashion in early 2020.

Furthermore, if the FCS facilitates entry into cells (as has been assumed by those who purport to understand such things), then it surely ought to be more virulent than SARS-1, as it presumably allows for faster spread within the airways themselves. Again, if this is the case, how did such a novel and deadly virus spread so far and wide and over months globally without being noticed before?

Clare Craig has argued (see here and here) that the surges occur not because of the virus per se, but because of a dramatic change in susceptibility to the virus—a so-called "seasonal trigger". It is true that host susceptibility to respiratory viruses is poorly understood, but there are many examples of neighboring locations that experienced vastly differing mortality outcomes despite sharing the same climate. So either the virus surge was highly geographically selective (unlikely) or another hypothesis explains the variation in outcomes and the excess death spikes.

In his second article, Jones attempts to explain “why, if it was in countries all round the world that winter, the explosive outbreaks only began in February and March 2020”. This is, of course, the very question we are asking. He says that “this is because the virus’s journey from first emergence in autumn 2019 to explosive outbreaks in early 2020 occurred in a slower and more staggered way than we might expect from a simple understanding of viruses. This is not because the virus wasn’t present in countries prior to causing explosive outbreaks there—that’s the simplistic assumption that is contradicted by the data—but because the virus doesn’t always cause explosive outbreaks when it is present.”

This appears to be a mere restatement, without explanation, of the core problem in his thesis—the implausibility in the way in which the qualities necessary to explain the mortality spikes appear to come and go. He gives the impression of thinking there must be a single explanation (the virus) for all observed outcomes, if only people would look hard enough to find that explanation (the virus). This assertion that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence cannot be falsified, but given it can be applied to any causal assertion it fails to discriminate between plausible and implausible explanations.

Instead we look to Occam's razor when evaluating whether the evidence at hand supports one hypothesis over others. All other things being equal, the simplest hypothesis with the fewest parameters that are consistent with the evidence should be preferred.

Whilst we accept that there are also unanswered questions in the alternative hypothesis, we would argue that it is more consistent with Occam’s razor. The default hypothesis involves a myriad of assumptions about dramatic changes in viral behavior in terms of pathogenicity and transmissibility that have never been seen before in any respiratory viral outbreak, and rests on new, unevidenced, assumptions about the way viruses evolve.

Viruses and society exist in a kind of adaptive symbiosis and one affects the other via complex and poorly understood interactions that evolve over time. Thus, when a viral infection spreads through a population, which itself responds by suddenly and radically adapting its behaviour, the effects of the virus become difficult to extricate from the effects of the societal response. However, if there is little evidence of viral pathogenicity before the behavioural change in the society, one must consider the possibility that at least some of the subsequent morbidity is attributable to those changed behaviours.

In respect of the alternative hypothesis it is obvious that the resources provided for and the management of health and social care services differ significantly geographically, as do the underlying political and societal structures controlling them. Hence, the way each society or location responds to change will differ. There are also historical precedents for such changes, especially if precipitous, to be extremely harmful, and that some societies may be more vulnerable to such changes than others. So it is not a huge stretch to conclude that it is possible that observed variation in outcomes is explained by variations in societal responses.

There are, in fact, numerous examples of responses that undoubtedly had the potential to elevate mortality. A non-exhaustive list includes medical staff absences while “testing positive”, postponement of surgery and treatments, blanket do not resuscitate (DNR) orders, policies restricting the use of antibiotics, the emptying out of ICUs, the effects of fear on citizens’ health directly or on the way in which healthcare workers responded, relocation of frail elderly patients and the substitution of normal care pathways with end-of-life treatments.

It must be emphasized that such policies will have adversely affected the outcome of both non-covid and covid patients. In respect of the latter, even those classified as ill with covid symptoms (ie respiratory) would have been affected. This is contrary to an assumption implied by the default hypothesis—that just because someone dies “from covid” their death was somehow unavoidable. The evidence of inappropriate treatment suggests otherwise.

Jones has implied that attributing all excess deaths to this societal response is an ABC (“Anything But Covid”) position. But this mischaracterizes the alternative hypothesis as one that claims that coronavirus infections do not lead to any deaths. The argument being made does not hinge on explaining individual deaths. Rather, it revolves around explaining societal mortality in excess of that typically reported. Coronaviruses have long been implicated as a cause of cases of severe respiratory illness that leads to deaths (in the frail) prior to 2020, even though routine testing for them was not previously performed, hence these deaths were rarely directly attributed to these viral infections. The common cold might be the ultimate cause of death in a frail elderly person dying of cancer or heart disease, but this would not be recorded as the primary cause of death. There is no reason to assume that coronaviruses ceased to be so potentially lethal for certain vulnerable people in Spring 2020.

Moreover, given that the number of people diagnosed with covid was substantially bolstered by over-attribution, via false positive covid tests and changes in death certification, it is plausible that a coronavirus was being misattributed as the direct cause of deaths when it was not.

It must be made clear that amongst the many things that we and other skeptics are not saying are that “viruses don’t exist”, “nobody has ever isolated this virus” or that “coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2 don’t ever kill people”. We are also not making any comments here about the covid vaccines. In fact, our commentary is restricted to consideration of the events in early 2020 and no later. It is only by examining what happened when the emergency was imposed on a previously stable societal situation that reliable conclusions can be drawn about the matter at hand. Later, prolonged healthcare disruptions, vaccinations, “variants” and reinfections (inter alia) dramatically complicate the picture, such that, whilst those periods are obviously important, they cannot provide much information about the origin of the pandemic narrative.

What we are imploring people to consider is this: given that the events of Spring 2020 which occurred in a few key geographically separate locations informed the extremely harmful global response, is the default narrative and hypothesis plausible, or should alternative hypotheses be tested?

If Jones accepts (as he surely must) that there has been:

some inappropriate treatment of persons considered (rightly or wrongly) to be “covid patients”, and that this caused some deaths which would not otherwise have happened; and

some additional mortality consequent to policies affecting the health of individuals including their healthcare, but not regarded as “involving covid”

… then it must surely also be accepted that at least some of the excess deaths observed would not have happened but for these factors.

Critically however, since we do not yet know what the quantum of these effects is, how can it be ruled out that together they account for all or nearly all of any excess deaths observed?

In conclusion, we should make it clear that we are not here taking Jones’ approach in insisting that we must be correct–to do so would surely be unscientific. Rather we are asserting that there are sufficient holes in the default narrative, in the form of contradictory evidence, that another explanation that may account for all or most of the excess deaths must be investigated and tested. This alternative hypothesis warrants sober and diligent assessment, without being dismissed as fanciful or subject to demands for consensus.

I agree with Annie. It is so hard for us non-scientists to grasp all the complexities. All we can do is try to read as much as possible from sources we do our best to assess as reliable. PANDA has been one of my main sources (the Daily Sceptic another) and I am extremely grateful for their work and commitment.

Very grateful for this thoroughly researched information asking critical questions fairly