The text and slides of my 19 November presentation at the Palace of the Parliament, Bucharest, Romania.

Complexity theory and the epistemology of centralisation

A constant source of wonder and curiosity for me is how complex our world is: ecologies, society, immune systems, the banking system, social order, climate—all of them are staggering both in their complexity and in the infinite potential that complexity implies for knowledge growth to fill the void of ignorance.

In complex systems there is no algorithm that you can run to get to a "right answer"—some reliable prediction of the outcomes that will flow from a shock to the system, or some forecast of how the system will evolve over time. The notion that such systems can be summarised by parsimonious models, and that such models can be used as tools to control them is entirely illusory. Utilitarians want to perform a calculation delivering an answer that maximises utility, or the general good, or public health, or whatever objective they have decided to obsess about at any particular juncture. But they’re mistaken. When we're dealing with complex systems and trying to solve problems in complex dimensions, the only route that can take us forward is the system of trial and error, also known as evolution.

Evolution is a process of creative conjecture and criticism. Ideas experimented with on the margin, implemented in a gradual and piecemeal fashion and tested by their real world results can slowly cause a complex system to evolve in a way that promotes human flourishing. A necessary condition for this is freedom, which top-down, one-size-fits-all approaches do not entail. And all of this is central to the very notion of the scientific method.

In the biological world, innovation takes place at the level of sexual blending of genomes, or less importantly, mutation, and the criticism takes place in the real world—by way of what is sometimes called a fitness test. Other domains of knowledge are no different. Deduction, design and linear thinking play no role. And the illusion that they do is at the heart of utilitarianism. This puts the utilitarian worldview squarely at odds with the very fabric of reality.

When policy and decision-making proceed not by evolution but by decree, the entire apparatus of science is co-opted into the service of one or another hierarchical stratum. Instead of addressing themselves to the project of error correction, scientific institutions become propaganda and public relations outlets for the wealthy and powerful, with their research output manipulated to serve not science, but the narrative of the day. The more loudly the real world tells these institutions that the narratives of the ruling class are wrong, the more dissent must be suppressed.

This insight led me to frame a simple heuristic, dubbed Hudson’s Razor:

The general rule of thumb is that if any problem is presented (1) as a global crisis (2) admitting only global solutions, and (3) amid silencing of dissent, then it is a scam.

Further patterns confirm this conclusion; for example, science presented as a consensus, instead of as an evolving project. Whenever you see something presented as "the science" or "a consensus", you should be on the lookout for a scam.

Economics of centralization

Centralization and utilitarianism are closely related to Stalinist political orientations—to central planning and to today’s fashionable "globalitarianism". In the world of finance, central bankers commit the centralist conceit when they maintain that is they who control economic growth, by way of interest rate manipulation, controlling the money supply, and so forth.

But the causal structure of economic growth is rooted in knowledge creation. In the same way that knowledge growth only plays out in a world of free ideas, economic growth only plays out in the world of free markets.

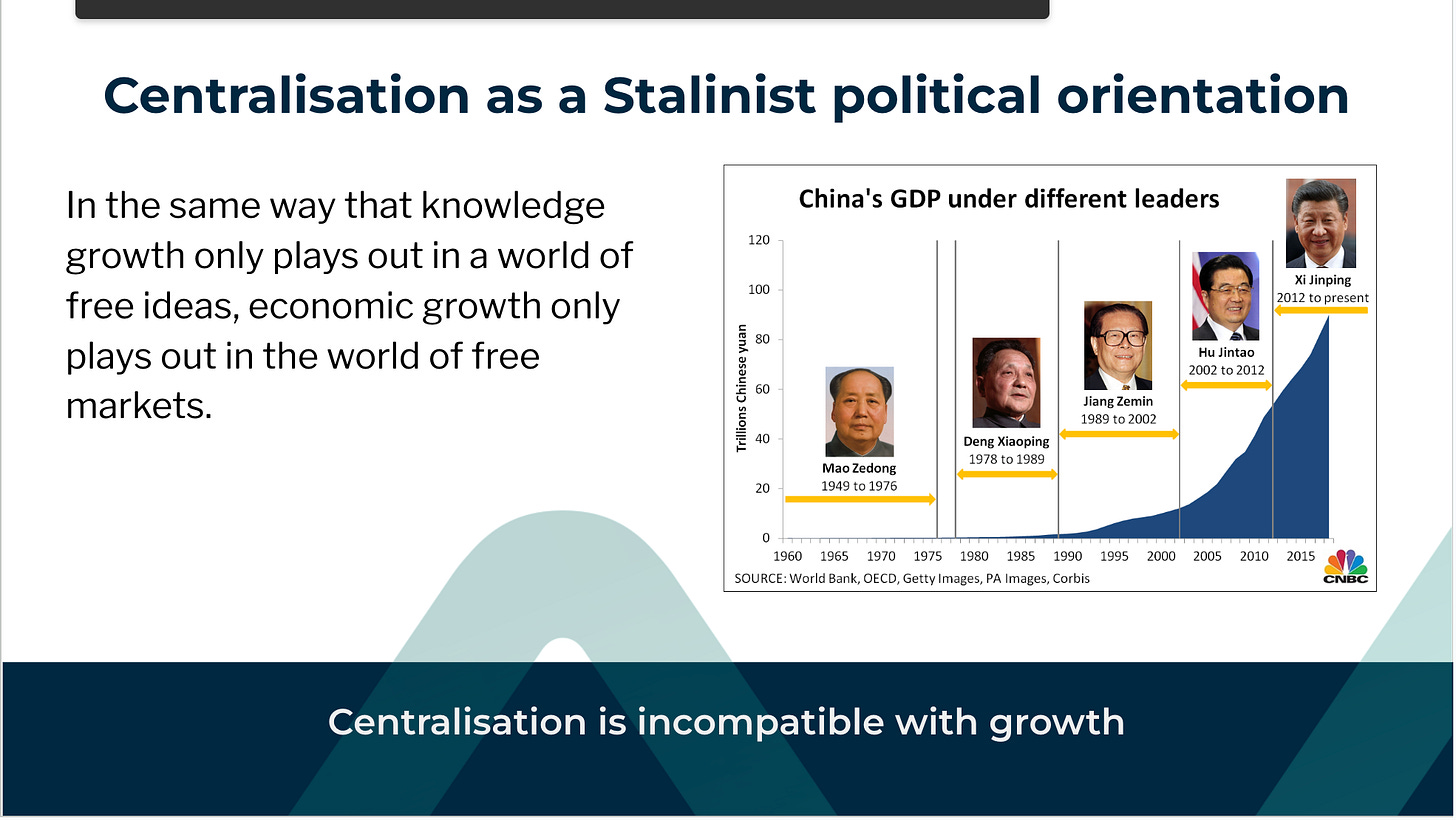

We see this proven time and time again throughout history. When Deng Xiaoping liberated the small and medium enterprises of China, he set off a multidecadal growth spurt that only slowed down when his eventual successor, Xi Jinping, began clamping down on that freer market. When the Soviet era ended, countries like Romania saw their real per capita output quadruple in a single generation.

I think that in their heart of hearts many centralists actually know that centralisation is incompatible with growth, but they still like it for ideological or criminal reasons. Certainly, we see members of the cult of globalism starting to talk about "degrowth", saying that we have to "end our addiction to economic growth".

This is quite sinister. If stopping economic growth requires stopping knowledge growth, then what they are intent upon doing is killing knowledge growth itself. They are telling us that they cannot abide innovation and problem solving. And they can only get rid of it by implementing a system of global control that ends all the liberties that inevitably lead to knowledge growth. Universally, the pretext for such control is the global crisis. I invite you to think about how commonly we are told that there is a new one.

Failure to comprehend the unlimited potential of knowledge to unlock new resources and solve human problems has a name, and that name is Malthusianism. The central tenet of Mathusianism is that the world is running out of resources. Every few decades or so, some freshly minted idiot somewhere puts a fresh spin on this feeble notion, only to see their particular prediction of disaster embarrassingly defeated by knowledge growth that they couldn’t predict. I hasten to add that they are not stupid because they can’t predict future knowledge. If it were possible to predict future knowledge, then it would be current knowledge. They are stupid because they are unwilling to perceive the reality that current limits to knowledge will only persist if their dream of stamping out growth comes to pass.

We forget that there are degrees of stupidity. I like to borrow David Krakauer’s example of that simple object, the Rubik’s Cube. The clever way to solve a Rubik’s cube is to devise algorithms—sequences of movements that bring the colours into alignment. There are simple algorithms that pay less attention to the starting condition of the cube, and then there are smarter ones that pay more attention to the starting condition and that are faster.

Another way to solve a Rubik’s cube is to program a robot to make random moves and to stop only when the puzzle has been solved. But this is really stupid because the number of seconds that is expected to take exceeds the number of stars in the observable universe. But even such a brute force approach does not attain the limits of stupidity. An even more stupid approach is to tell that robot to keep turning one side of the cube until the puzzle is solved. No matter how long you give the robot, that approach will never yield a solution.

And it is into this extreme category of stupidity that centralists fall, because their method for approaching human flourishing is entirely at odds with reality and would indeed stamp human flourishing out.

Because of this Inconvenient Truth, centralists like to form clubs that non-centralists aren’t invited to. And so we have the Club of Rome, the Collegium Internationale and the World Economic Forum, to name a few. And they get together at these clubs and they co-author long documents with titles such as “The Limits to Growth”. And they come up with plans to impose controls over the global population. And they invent Global Crises that admit only Global Solutions, and plans to suppress dissent against those proposed Solutions.

But as the decades roll by and as their Malthusian predictions sequentially fail to materialise, they become frustrated. By the 1970s we can see them realising that they lacked the capacity to influence people into accepting centralist gospels, and stumbling upon the idea of scaring people into compliance by fabricating invisible threats. We can trace them identifying two promising prospects: pathogens and global cooling. When global cooling fails to materialise we see them switch to global warming, and when that fails to materialise, to the vaguer “climate change”. Half a century later, the inexorable knowledge growth that they refuse to incorporate in their models delivers a new prospect: a set of threats related to AI.

And along the way they add various Mathusian bogeymen: peak oil, and shortages of top soil, of water, of rare earth metals, and, of course, of food. At each juncture they encumber these pessimistic visions with strange diagrams posing odd relationships between these purported tragedies, amid an endless word salad that thinly conceals their stupidity.

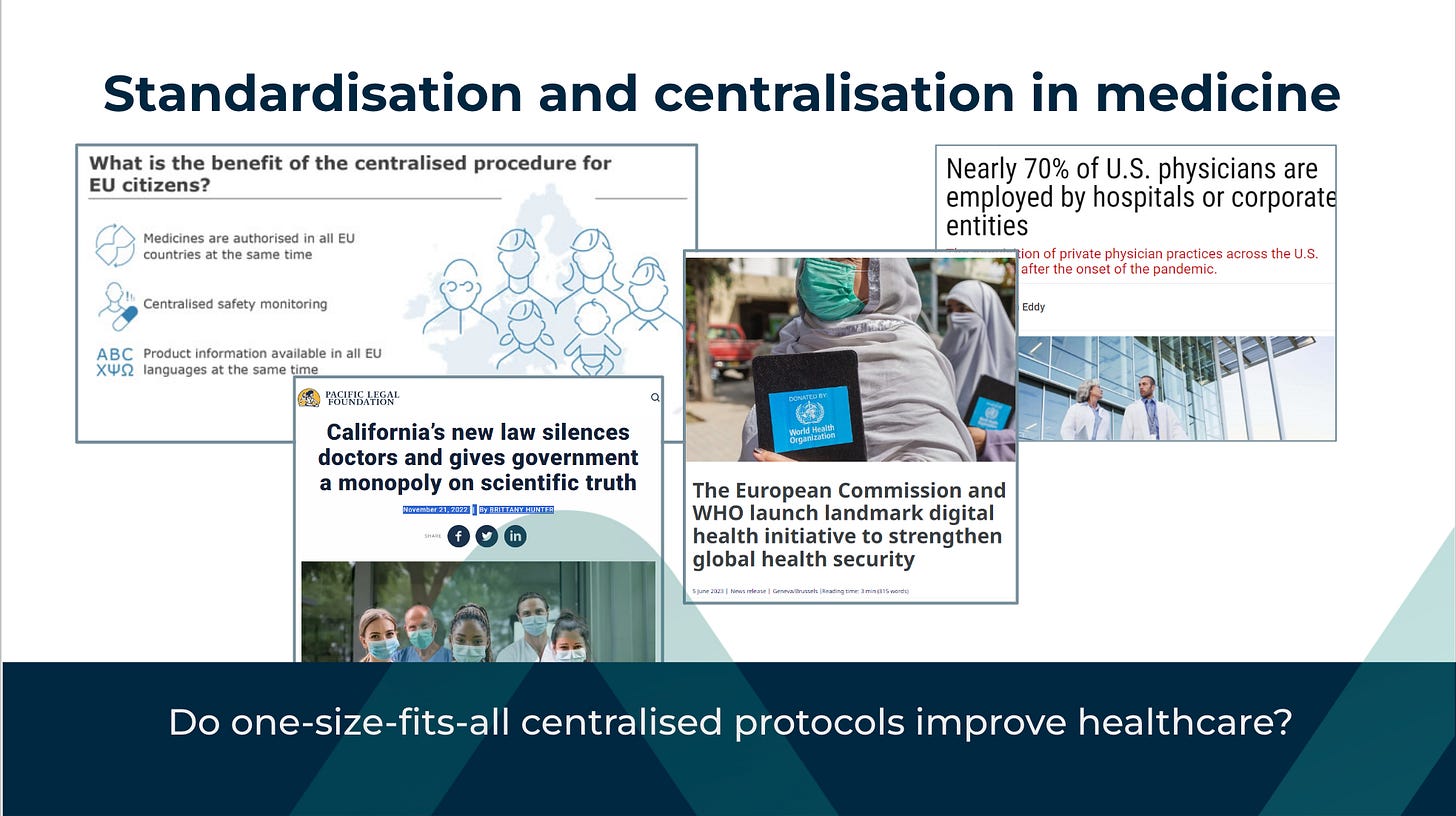

And their ambitions grow. In public health they want to see the WHO expand and implement a top-down system called One Health, where all health solutions are to be found in pharmaceutical products. And they want to force global adherence to One Health through a new Accord and set of International Health Regulations that they plan to see signed in the next few weeks.

In medicine they enforce standardisation through the euphemism of evidence-based medicine and treatment protocols, with doctors who won’t apply those protocols being subject to having their licences revoked.

In economics and finance they advocate the marriage of central banks and the State, instrumentalized through programmable central bank digital currencies, which they will also use to enforce control in other domains. They invent Modern Monetary Theory to explain away the harms from the perpetual theft that central bank fiat currencies and unconstrained borrowing entail.

For the food industry they dream of a future where small farms are replaced by very big ones growing monocultures using the same seed stocks, and where the eating of meat is replaced by the eating of insects.

In information technology they want to manage ‘permissible’ content, implement mass surveillance, digital IDs, vaccine passports, social credit systems and regulations that would prevent AI from accidentally exposing their propaganda for what it is.

In energy they want to pursue net zero, a system that if implemented would be guaranteed to see energy budgets plummet, and half the world starve. And they dream of digitised controllable infrastructure.

In teaching they advocate for outcomes based education, with Unicef-standardised syllabuses encouraging narrative regurgitation and discouraging the critical thinking that would be sure to see children growing up into adults that see through their stupidity. The very reason for the existence of my talk today is that they have had some success in expunging the ancient knowledge of how disastrous centralisation is, from all of these fields I have mentioned.

Zero-sum geopolitics

Where this kind of Malthusian centralist thinking attains its most destructive pitch is in the domain of geopolitics. The psychology of scarcity is quick to drift into zero-sum game mentality. The most obvious one is the simple fight to command resources—gold, oil, rare earth metals or arable land. But a more pernicious version involves purposeful destabilisation of other parts of the world, with the idea being to stop their growth and therefore their increased consumption of resources in the finite world that globalists perceive.

Ethics of subsidiarity

The counter to this is the doctrine of subsidiarity, which states that it is immoral to take decisions at a higher level in a hierarchy when the problem involved can be solved at a lower level. This is the essence of decentralisation. It does not propose the radical atomisation of libertarianism, or ignore the fact that we are social animals who do well when we cooperate and coordinate.

Subsidiarity is not a guarantee that decisions will be perfect. But whereas centralisation tends towards one-size-fits all solutions, which can only fail, subsidiarity builds in the flexibility to react to local issues dynamically. With different solutions being attempted in different places, the evolutionary process of conjecture and criticism is invoked. And because poor decisions are not universal, the totality of the complex system subsidiarity fosters is less fragile. Failure is less catastrophic and error correction swifter.

Subsidiarity also creates a microcosm in which individual participants can make out a line of sight between their actions and consequences for themselves and their immediate community. A sense of meaning and purpose is more likely achievable, relative to the profound alienation that accompanies the realisation that one is merely a cog in a giant machine. With meaning and purpose comes a sense of responsibility and accountability, which is not surprisingly missing from our world of narcissistic identity politics.

Subsidiarity as a model has deep roots in Catholicism, having been the subject of three papal encyclicals over the course of 150 years. It was also a founding principle of the European Union, the dawn of which was accompanied by fears that member countries would be forced to spurn their individual cultures, but the term has fallen out of use as that organisation has done precisely what was feared. The present pope, cleaving to Jesuitical centralism, would now undermine subsidiarity, showing how far and wide the morally indefensible vogue for globalism has extended.

But I contend that subsidiarity holds the key to resisting the centralist impulse and keeping alive the flame of human agency, and it is therefore something we should all cherish and promote at every opportunity, at every level of societal hierarchy and in every sector and domain. Delegating authority requires humility and wisdom, and I wish both to you in abundance.

Thank you.